Connecting The Dots

Is human agency within domestic civil society totally disassociated from the anarchy that exists on an international scale between states and does that explain the political apathy among citizens in a semi-periphery developed state like Singapore? Most in Singapore would agree with this, as they don’t feel the direct impact of politics and state relations in their daily lives.

However, I would like to explore how the liberal-based harmony of interest and interdependence or realist self-interested tendencies manifest in individuals’ daily life in Singapore. While there are other examples to compare human agency and the international system of states, I will be focusing on Singapore’s education system as a core example. The concept of statecraft at hand to be dealt with will be the security dilemma.

What Is The Security Dilemma?

The security dilemma is a concept revolving around a zero-sum game fuelled by mutual suspicion between actors in a system. International relations scholar John Herz detailed this paradoxical concept where the self-interested behaviours promoted by the anarchical international system pushes states to look out for their own security needs over others. This, in turn, breeds insecurity among other states who view this measure as potentially threatening, in spite of its docile or neutral objective. American political scientist Robert Jervis encapsulated how insecurity stems from a mindset that any action “benign today, can turn malign in the future”. According to Charles Glaser, this also extended to the various states’ positions on nuclear policy.

I argue that the security dilemma arises from a fear of missing out (FOMO) between states. Viewed through the lens of a zero-sum game, a neighbouring state gaining or increasing its security capability is not merely seen as a defensive action, but an offensive one that puts the home state at a disadvantage. States in this system put their self-determination above another to thrive in this system.

A classic example would be the nuclear arms race that culminated at the height of the Cold War. Achieving nuclear capability is seen as reaching the “highest” state of offensive potential a state can achieve, as two states with nuclear capabilities – if hostile – are in a stalemate of mutually assured destruction (MAD). However, merely achieving nuclear capabilities was not enough as it became a race to the top, due to the zero sum nature of the international system.

States with the capability to, will pursue nuclear options. The converse is true, with states unable to accept the fact and find alternatives around nuclear proliferation.

Tuition, An Everyday Security Dilemma

Now, you might be asking yourself why you just read an entire paragraph about politics that has nothing to do with you in daily life. However, I would like to extrapolate this example into a Singaporean context. Take, for example, the phenomenon of “Kiasuism”. Defined as a selfish behaviour arising from FOMO, the Hokkien phrase describes the FOMO felt between states internationally, as the ever-present thriving “Kiasuism” felt by parents as they pit their children against each other. I’m sure that most of us who have grown up in the Singaporean education system can attest to the overwhelming FOMO that fuels all actors concerned in a child’s journey in the education system – parents, teachers, schools, tuition centres, and teachers.

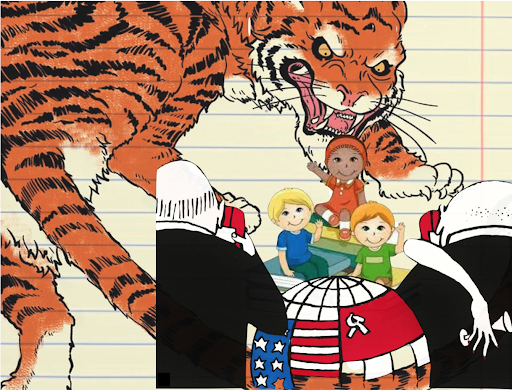

We can draw comparisons between the two if we view students as states and tuition as nuclear weapons, with the school and national examinations being the international system where “Kiasuism” or FOMO is bred. Students and their parents are actors who represent the state, and their mutual suspicion towards other states is the anarchy in the international system of states. The competition for power in the international system is mirrored by the competition between students to see who can achieve the highest grades.

These two different types of competition mirror the zero-sum nature, in that there can only be one winner after aggregation. In the competition between states, an arms race for nuclear capability. In the competition between students? A race to the top for the highest grades. Those who are unable to achieve nuclear capabilities languish along the sidelines or find an alternative means to stay relevant in the conversation. This is further supported by the zero-sum nature of the “international system” that uses a bell curve to aggregate students across their cohort, where students are pitted against each other and for one to perform better than another, they have to perform poorer. In a dog-eat-dog environment, those who can, will.

China’s Rejection Of “Capitalism” In Education

Let’s take a look at China’s recent social crackdowns on tuition, and how this approach differs ideologically from the FOMO in Singapore. The arms race of the security dilemma and the urge parents feel to send their kids for tuition or enrichment classes are fuelled by the same thing: FOMO. Could this self-interested, power-hungry behaviour be just a hallmark of classical realism where unequal gains are made in a zero-sum environment? Or will we find other underlying reasons in China?

In China’s recently suppressed private education system, over 3 million jobs are at risk in this dying sector that grew 79 per cent from 2016 to 2019. Adopting the emancipatory lens of Marxism, China’s actions are a critique of an education system that has been polluted by the “freehand of the market”. Instead of pursuing education as a noble cause, children and parents alike are being pushed by the “invisible hand” of the market via FOMO to equip each child, not that they should excel, but that they do not lose out.

In China, President Xi Jinping is seeking to be the force that breaks this convention, in an effort to preserve the “Chinese Dream”, a rejuvenation of China’s economy and ideology of socialism with Chinese characteristics on an international scale. Tanner Greer, an independent researcher and writer who has consulted governments on foreign policy, touched on this in his 2021 article “Xi Jinping’s war on spontaneous order”. He elaborates that the preservation of the “Chinese Dream” comes in the form of crackdowns aimed at breaking the generational cycle of cultural dependency on the west influenced by video game developers, executives, and admen – All responding to a system that incentivises this behaviour in a “Capitalist system”.

Is The Education System A Zero-Sum, Or An Infinite-Sum Game?

As we’ve discussed before, similar to the security dilemma, education is also a zero-sum game. However, is the education system also really just a hopeless zero-sum game?

To elaborate on this, we first need to dissect whether the education system should be one that cultivates learning and specifically a self-learning mindset, or one that incentivizes students to score better than every other individual to determine their proficiency in the subject matter. If it’s the latter, it closely resembles the aforementioned arms race.

We also need to explore what are other methods to measure students’ success, besides the popular bell curve that seeks to aggregate the total populations of students relative to each other and distributes grades across the cohort. It effectively makes the grading system for education at any given point of time a zero-sum game as it compares grades relative to an entire cohort of students, and the average performance of these students. However, it pits the students against each other, as it is no longer in each student’s interest to see each other thrive as their gains are relative. If one wins, someone else has to lose.

However, that is not the case in real life. As Thomas Reid says, “The chain is only as strong as its weakest link, for if that fails the chain fails and the object that it has been holding up falls to the ground.” Why would a sports team intentionally want to sabotage their teammates? If in battle, why would a soldier want their partner that has their back to not be incentivized to do their best? In reality, this method of applying a bell curve does not foster cooperation between individuals, but rather promotes a general sense of animosity and distrust.

This is akin to a Hobbesian state of nature – where no one else can be trusted except oneself and thus self-interest has to be prioritised, which fosters no sense of communitarianism. This might be a troubling notion as this sense of animosity is being bred into the youth of nations through the education system that seeks to weed out the best from the rest.

Breaking The Cycle Through Collective Action

Ultimately, we need to be aware of how FOMO influences and shapes perception, be it through states navigating the international system, or amongst individuals impacted by the education of a state. How we view these institutional systems in daily life, will in turn affect how and what we choose to pour our attention to in daily life.

Furthermore, I firmly believe that just because the system is rigged to be zero-sum in nature, that does not leave individuals helpless against it. Instead, as a collective, individuals can change and influence perceptions within the constraints of the system from a bottom-up approach through civic endeavours. This should be seen as a call to action, for us to step up and truly act on the changes we want to see instead of being caught in a loop manifesting change.